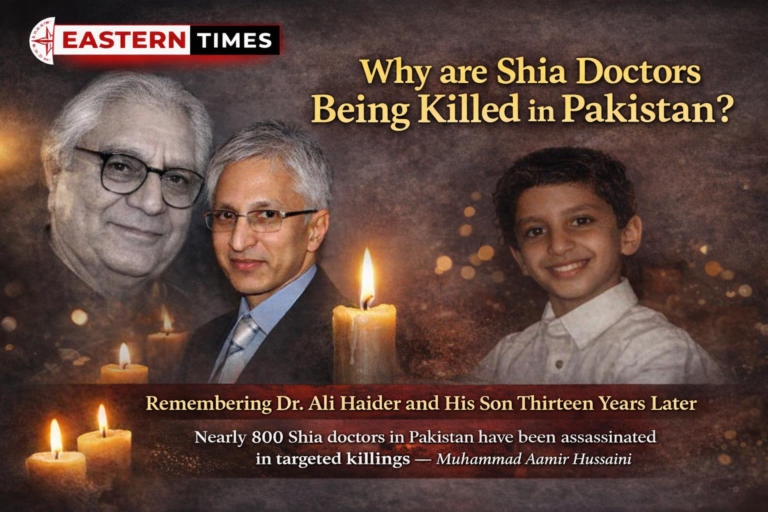

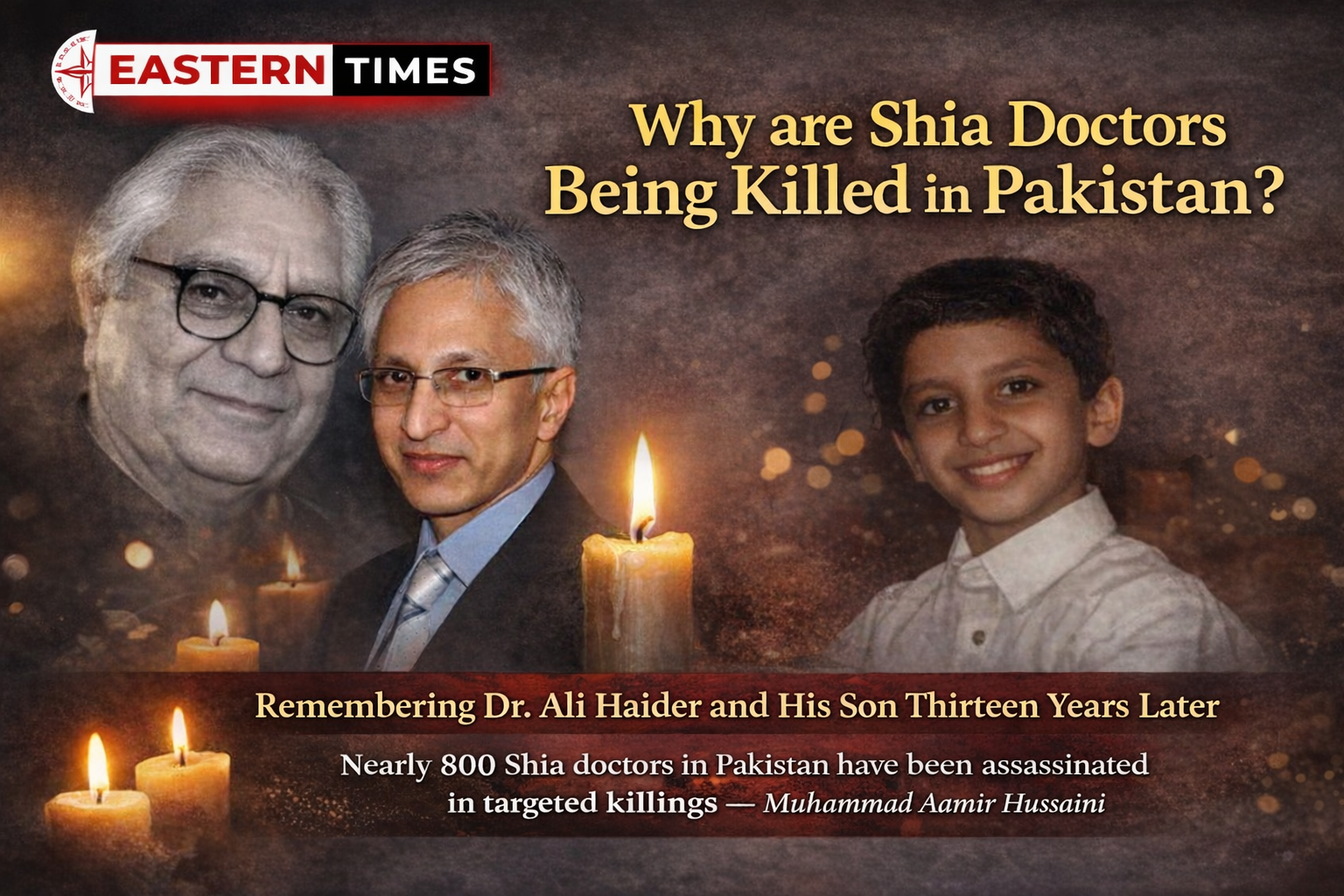

Note: Nearly 800 doctors in Pakistan have been victims of targeted killings solely for being Shia. Behind each of these murders lies a deeply tragic and human story—families shattered, children orphaned, communities left in fear. According to data available on the Muslim Shia Genocide website, approximately 2,500 highly qualified Pakistani Shia professionals have been assassinated in targeted attacks. The same source documents that over the past three and a half decades, more than 25,000 Shia Muslims in Pakistan have fallen victim to targeted killings.

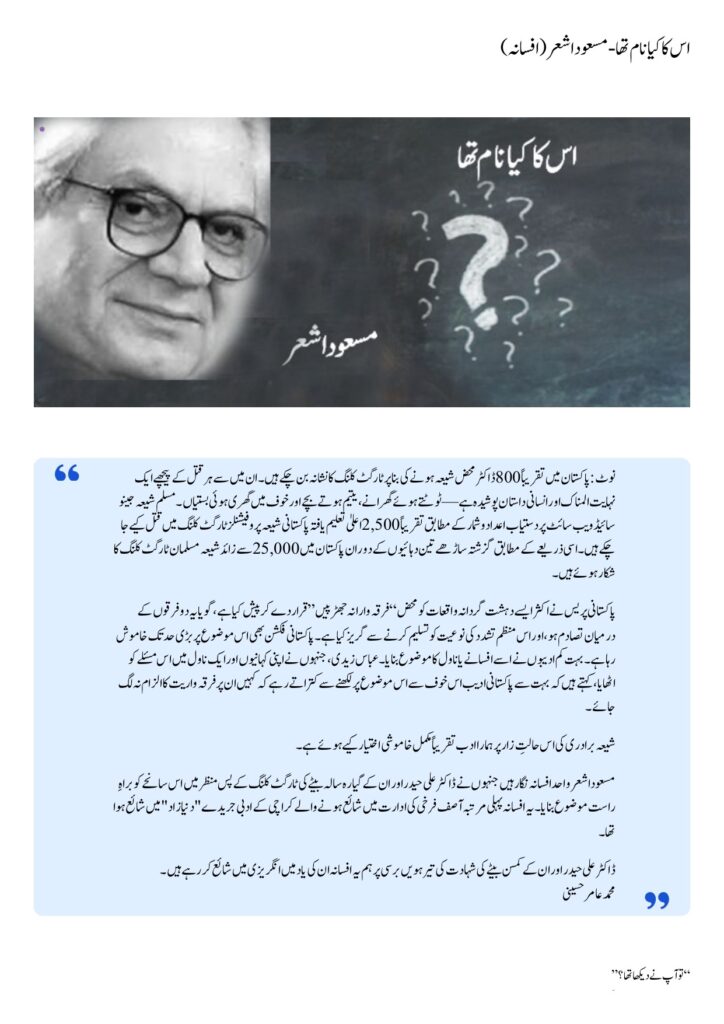

Much of the Pakistani press has often reduced such acts of terror to mere “sectarian clashes,” framing them as a conflict between two sects rather than acknowledging the systematic nature of the violence. Pakistani fiction, too, has remained largely silent on this subject. Few writers have chosen to make it the theme of a short story or novel. Abbas Zaidi, who addressed this issue in his short stories and a novel, has observed that many Pakistani writers avoided the topic out of fear—fear of being labeled sectarian themselves.

On the suffering of the Shia community, our literature has remained almost entirely mute.

Masood Ashar stands as the only short story writer who directly addressed this tragedy in a work set against the backdrop of the targeted killing of Dr. Ali Haider and his eleven-year-old son. The story was first published in the Karachi-based literary journal Dunyazad, edited by Asif Farrukhi.

On the thirteenth anniversary of the martyrdom of Dr. Ali Haider and his young son, we publish this story in English in their memory – Muhammad Aamir Hussaini

“So—you saw it?”

“Yes, I saw it. But…”

“But you didn’t stop there, did you? Because such incidents happen every day. It was just another incident—a news item for the newspapers and TV, wasn’t it?”

Whenever you meet them, the same questions and answers are repeated. And each time, you feel like a criminal.

“Ever since the underpass construction began, I’ve been taking that route. That day too, early in the morning, I passed by and saw some people standing on the bridge, gathered around a car. There were two or three policemen there as well—traffic wardens…”

The first day, you tell them all this, and holding back their tears they say, “Yes… it could have been a traffic accident, couldn’t it? That’s what you must have thought?”

You lower your head and cast your eyes down—what else can you do? What else are you capable of doing? You can do nothing—no one can do anything. When you try to console them, you know very well that you are lying. You know that every person’s grief is their own, personal and private. No one else can truly share in that sorrow. Those who speak of sharing someone’s grief are deceiving others—and themselves. Yet even knowing this, you keep talking. Because if you stop speaking, they will begin. And you do not want them to speak. They will ask you only one thing, again and again: “So—you saw it, didn’t you?”

And when you give the same answer you have already given countless times, they fall silent for a while. Then they ask another question: “You know, don’t you… what his name was?”

They do not want an answer. The question itself is the answer. You remain silent.

“It was his name, wasn’t it, that…” Their voice chokes.

Then they remember the slugs. The slugs—that black, slimy creature that suddenly appears in a lush green lawn and begins devouring flowers and leaves. Wherever it goes, it leaves behind a sticky trail—a silvery, glistening line. A sticky and poisonous line. “That morning… it was early morning, wasn’t it?” They ask as if they have forgotten that it was indeed morning. “He was taking his son to school. That day his son was going to receive a prize.” They take a deep breath. “I was standing in the lawn, looking at the slugs. I was worried about how to get rid of those disgusting, crawling creatures. And then—just then—people came running and stood in front of me. They said nothing with their mouths, but my heart seemed to stop beating. Their faces, their eyes, said everything… I sat down right there. Then they were saying something—but it wasn’t my ears that were listening, it was my heart. Everything…”

They speak, and you listen silently with your head bowed. They have repeated this story so many times that even saying “Yes” feels pointless now.

The school calls: come and take your child, he has been hurt. You rush there. It is a junior school. There is only a small scratch on your child’s head. “He pushed me,” your own child says, pointing to another boy his age. You look at the other child. The teacher is trying to explain something to you, but your attention is more on that boy—who is crying even harder than your own child. Your child is quiet now, as if your presence has reassured him. You hand your child back to the teacher and go to the other boy, placing your hand on his head. The boy clings to you and begins sobbing uncontrollably. You comfort him. Then you say to your own child, “Be brave, son. It’s just a small scratch. Who cries over such a tiny injury? Come, hug your brother.” Then you say to the other boy, “Hush now, hush. Nothing happened. It was just an accident, wasn’t it? Your hand just brushed against him?” The boy does not look at you; he keeps looking at your child. “Yes… my hand just touched him…” And the teacher stands there smiling.

Years later, in a hotel lobby, a young man with white hair comes and stands before you. “Peace be upon you, Uncle.”

You look at him carefully and recognize him. “Oh—how did your entire head turn white? And so soon?”

“We often go to your house to meet your father—but we never see you.”

“Well, you go to meet Father, don’t you?”

And it is true—you go to meet his father. And that too at night. Like well-brought-up children, he does not sit in gatherings of elders. You already know he has become a very big doctor now. Very busy. Very famous.

That day, between the afternoon and evening prayers, you go to their house. The large gate opening onto the road is pushed shut in such a way that anyone can lift the latch and enter. It is an old-fashioned gate—from a time when gates were not more than four or five feet high. In those days, such gates allowed you to see inside and out. Gates higher than six feet have only begun to be built recently—ever since people started fearing even themselves. After the incident, you had told the servants to keep the gate locked from inside. Anything could happen at any time. Even that day, you scold the servant about it.

“Shah Sahib says to keep the gate open. Now it’s my turn—let them come. I’m ready too,” a servant tells you, eyes lowered.

You go inside. Your first glance falls on the one-kanal lawn, once famous throughout the neighborhood for its beauty. Now it looks like a ruined wasteland. It is April, yet the petunias, daisies, pansies, and sweet peas look lifeless. The grass seems dry, as though it has not been watered for days.

“Doesn’t the gardener come?” you ask.

“He comes—but Shah Sahib has ordered that the lawn not be watered. If the lawn is damp, slugs come,” the servant replies.

As you move forward, you see a shadow behind a small orange tree. He is sitting on a chair, offering his prayer—the Zuhr and Asr prayers. All the buttons of his shirt are open. The sleeves hang loose from his arms. The blood seems drained from his face; he has turned pale. Something tightens in your heart. What has happened to him in just a week or two? And why is he praying while seated? There is nothing wrong with his knees. Just a week ago he was standing in the operating theater for hours, performing delicate and complicated surgeries. Thyroid surgery is extremely intricate and difficult—he was renowned across the country for it. Patients came from far away for his operations. Only last week he had operated on your colleague.

But—his hands are trembling? You look at the hands resting on his knees. They are not merely trembling—they are quivering, writhing. It is difficult for him to keep them steady on his knees. Intense anguish is visible on his face. You stand there with your hands folded, as if you yourself are praying.

Now he sees you. He says nothing. He walks inside toward the drawing room. You follow him. Seating you on a sofa, he goes into another room. You sit there. His wife comes in. Her once rosy-white face looks innocent and simple. Around her eyes are not dark circles but red patches. The whites of her eyes are red, as if blood might drip from them at any moment.

“Do you know why he went inside?” she asks. You remain silent, knowing she will answer her own question. “He doesn’t want to cry in front of anyone. Not even in front of me—he goes into the bathroom.”

You say nothing.

“Because of him, I can’t even…” she says, covering her eyes with her dupatta.

“At night he keeps turning from side to side and asks me again and again, ‘You’re not crying, are you?’”

Now you, too, hide your eyes.

“When the resolution was passed, my father was present at Minto Park. He used to tell us stories of that day—what passion, what fervor—”

A few days later, when you visit again, he begins speaking of old times. He starts but stops midway, as if struggling to control his surging emotions.

“In the 1946 elections, my father toured all of Punjab and the Frontier,” he says. “Our entire family was in the Unionist Party. But my father alone stood with the Muslim League. You know, don’t you, my father was a lawyer? The most respected and renowned lawyer in our area?”

A woman brings tea, pours it into cups, places one before you and one before him. She remains silent throughout.

“When refugees, looted and ruined, came here from East Punjab, our family gave them shelter—” He suddenly strikes both hands against his cheeks. “Astaghfirullah—who are we to give shelter? The One who gives shelter is He alone. We only fulfilled our duty. Who were those refugees? What were they? It did not matter to us. For us, they were refugees—people who had lost everything and were coming here.” He looks toward the ceiling, as if trying to read something written there. “If we took or gave anything…”

Again he holds his ears. “Astaghfirullah. You know us well.”

You give no reply.

“And then what happened…?” He tries to lift the cup with trembling hands. The tea spills. He places the cup back on the side table. You do not touch yours either.

You begin looking at the photographs on the wall. There is one of him too—no longer in this world, yet present everywhere—standing with his twelve-year-old son. Another photograph: bride and groom. When he married, many were surprised that the girl was not from his sect. But you were not surprised; that was the kind of family they were. In fact, you were not even surprised when his brother’s daughter married someone from another sect. Both marriages were very successful.

“They eat the new shoots,” he says suddenly.

He remembers the slugs again. He, too, was like a new shoot. What age was he, after all? Is forty or forty-five even an age to die? And at that age he had gained such fame that patients came from other cities for treatment.

He falls silent, biting his lips.

He treated the poor for free. Twice a year he set up camps in his ancestral village. He operated on everyone. Gave new sight, new eyes, to all—without discrimination. And—and—that twelve-year-old child—what was his crime? Only that his name also…

His eyes are fixed on the ceiling. That child was going to receive a prize that day. He was taking him to school…

Now he fixes his gaze on you. “You know, don’t you—what his name was?”

“It was his name, wasn’t it, that took him and his twelve-year-old son—”

Silence fills the room. His wife rises and goes into the other room. The two of you remain alone. He stares at you. You look at the photograph of the white-haired young man and his child, who that morning had been going to school with his father to receive a prize.