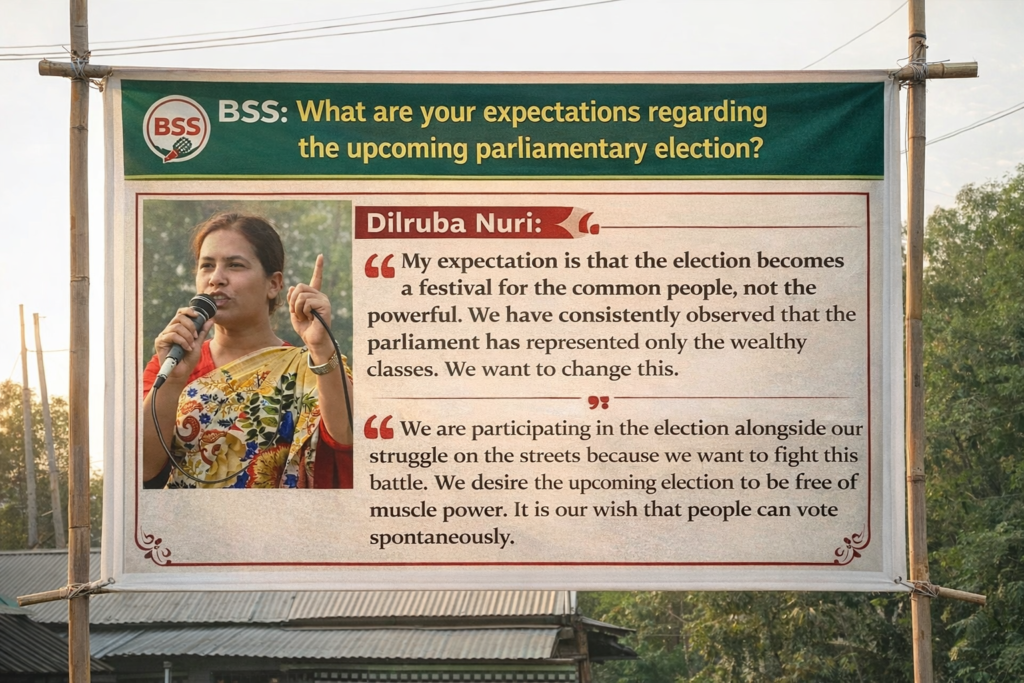

With a Handheld Loudspeaker, Dilruba Nuri Takes On Money, Patriarchy and an Unequal Election

In the narrow lanes of Bogura town, a striking campaign scene is unfolding: a woman walking door to door with a handheld loudspeaker, speaking to voters one street at a time. She is Dilruba Nuri, 38 — the only woman contesting the Bogura-6 (Sadar) seat in Bangladesh’s 13th national parliamentary election. In a constituency of nearly 450,000 voters, her campaign runs not on wealth or spectacle, but on footwork, volunteers, and small donations.

Election campaigning entered its final day today, with Dhaka witnessing rallies by senior leaders of major political parties, causing traffic congestion in parts of the capital.

Among 34 candidates competing for seven parliamentary seats in Bogura, Nuri stands alone as the only female aspirant. She is running with the “Ladder” (Moi) symbol as a nominee of the Democratic United Front, an alliance of nine left-leaning parties. A lawyer by profession, she is a familiar face on Bogura’s streets — walking from house to house, urging people to vote not for handouts but for rights.

A Campaign Built on Steps, Not Spending

Nuri’s approach is simple and relentless: reach as many voters as possible, personally. Yet she knows the arithmetic of the field is brutal.

“I want to reach every voter,” she says, “but even if I walk from dawn to dusk for all 18 days of campaigning, it is impossible to cover 450,000 voters.”

When she can, she rents a pickup van to expand her reach. But the cost is crushing. According to her, renting a pickup and three sets of loudspeakers costs around Tk 6,000 a day — an amount that quickly becomes unattainable for candidates without wealthy backers.

The Money Wall in Electoral Politics

The election rules allow candidates to spend up to Tk 10 per voter, which for Bogura-6 translates to roughly Tk 45 lakh. Nuri asks a question many ordinary candidates carry quietly but rarely say aloud:

“Where will I find Tk 45 lakh? And who are these candidates spending unlimited money on campaigns?”

For her, the spending ceiling is not a guardrail — it is a mirror reflecting how the system is built to reward money. She argues that the cost of campaigning itself has turned representation into an elite privilege.

“How can an ordinary person compete with wealthy candidates?” she asks.

Nuri alleges that many well-funded contenders are major bank borrowers or even loan defaulters.

“They are effectively using public money — unpaid loans — to finance their campaigns,” she claims. “State policies favour the rich, while the working class and women are reduced to voters, never representatives.”

From Student Politics to Socialist Women’s Organising

Nuri entered politics in 2003 through the Samajtantrik Chhatra Front. Since 2022, she has served as the district member secretary of the Socialist Party of Bangladesh (BASAD) and as the central general secretary of the Socialist Women’s Forum.

Her political motivation, she says, is rooted in the daily realities of working people — especially those living in what she calls inhumane urban conditions. For her, politics is not a ladder to personal power, but a fight for basic dignity.

“Work for Every Hand, Rice for Every Mouth”

Her manifesto’s main slogan is direct and memorable: work for every hand and rice for every mouth. Alongside economic security, it pledges a discrimination-free society and a dignified life for all.

But she is clear that the struggle is not only economic. Gender bias, she says, runs through public life — including the campaign trail.

“Even during campaigning, voters question how female leaders and activists dress,” she notes — an everyday reminder that women in politics are still evaluated for appearance before ideas.

Voters Asking for Cash — and a System That Normalised It

Nuri also criticises a culture where votes are treated like commodities.

“People often ask for money when we ask for votes,” she says. “How did this system come to exist?”

To her, this is not just a voter problem — it is the consequence of a political economy where elections have been shaped by patronage, cash, and the expectation of immediate private gain rather than collective public rights.

“We want to be elected to give people a life of dignity and humanity,” she says. “Not an inhuman life, lived like beggars.”

A Lone Woman Against a Familiar Machine

Dilruba Nuri’s campaign in Bogura is not simply a local contest; it is a portrait of structural inequality inside electoral democracy. On one side stand money, entrenched power, and patriarchal scrutiny. On the other, a lone woman with a loudspeaker, walking street to street — insisting that representation should not be auctioned to the highest bidder.

Whether she wins or not, her candidacy has already forced a question into the open: Who gets to be a representative — and who is allowed to remain only a voter?