Spiritual Continuity or Historical Dialectics?

A Critical Appraisal of Punjabi Progressivism

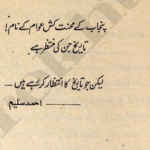

This essay is not the product of a fresh idea; rather, it is the recovery of an intellectual experience buried beneath the layers of time. A piece written in the 1990s by Asif Khan—then Chairman of the Pakistan Punjabi Adabi Board, Lahore—titled “Alif Allah”, which in its day was not merely a literary text but a symbolic intellectual intervention, suddenly reappeared before me. I was sorting through my old papers when a yellowing photocopy came into my hands; alongside it were my handwritten lead-off notes prepared for a study circle. It felt as if it was not paper that had opened up, but time itself—as though an entire era, long sealed within the closed layers of memory, had begun to breathe again.

I remember clearly how charged with enthusiasm and intellectual restlessness those days were. We had started a study circle in Lahore in which a dozen or so students from various educational institutions of the city participated. This was not a formal exercise in reading, but an intellectual laboratory—an audacious attempt to examine how texts ranging from the Rig Veda to Sufi writings—that is, the foundational religious, mystical, and philosophical texts produced from the tribal society of Sapta Sindhu through to feudal society, authored in Punjab by Sufis, sadhus, saints, gurus, and Brahmins—could be read and evaluated through the lens of the materialist dialectical method of historical inquiry. In essence, it was a critical study of that tradition of Punjabi nationalist historiography which freezes social and class contradictions behind the veil of spirituality, unity, and sanctification.

During those days, a close friend and I also met with living progressive and Marxist intellectuals based in Lahore. We hoped that respected figures such as Safdar Mir and Eric Cyprian might help guide us in formulating a study-circle curriculum on this subject. But the outcome was disappointing. Either these questions lay outside their intellectual agendas, or the progressive tradition of that period itself hesitated to confront issues that would place religion, mysticism, and nationalist culture in the dock of materialist dialectical critique.

Consequently, we undertook the task ourselves—one that perhaps no one else was willing to assume. To the best of our abilities, we formulated principles for a materialist dialectical study of history, tested them in practice, and on that basis compiled a supplementary curriculum for the study circles. Guided by this framework, we prepared lead-off presentations, raised questions, opened up texts, and then conducted the study circles. We managed to hold five such circles in succession. After that, circumstances suddenly took a turn: I had to move to Karachi, and the process was cut short by unforeseen contingencies.

Thereafter, events unfolded with such rapidity that this entire experience—this intellectual pursuit, this questioning—faded into the haze of temporary forgetfulness. Today, years later, when these papers resurfaced during the same haphazard sorting of old documents, a flood of memories came rushing back. This was not merely a retrieval of the past; it was the return of an unfinished intellectual question—the very question that still stands before us with undiminished urgency: Do we truly have the courage to read our sacred texts, our spiritual traditions, and our national history through the lens of a materialist dialectical consciousness of history?

Asif Khan’s essay “Alif Allah” begins roughly as follows:

The Friends of God (the Allah-lok) have given extraordinary importance to the letter Alif:

One who has studied Alif

never needs to read the chapter of Be

Those who found their true state through Alif

never read the entire Qur’an — Sultan Bahu

Bulleh Shah says:

Read the one Alif and attain liberation,

Only that single Alif is what you need.

Alif alone is enough for me, O my beloved,

All other tales are of no worth.

Khawaja Ghulam Farid says:

Alif entered my heart and stole it away, O beloved.

Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai says:

Read the letter Alif and forget all pages,

Cleanse yourself from within—how many pages will you keep reading?

Sachal Sarmast says:

Your door requires contemplation through letters,

From a single Alif arise the meanings of a hundred letters.

In the Gita (Chapter 10, Verse 33) it is said:

Among letters, I am Alif.

In the Aitareya Aranyaka, Chapter 3, verses 2, 3, and 4, it is written:

The essence of all letters is the letter Alif.

A question naturally arises: Why did all these God-realised people give such greatness and exalted status to this single letter Alif, when there are so many other letters as well?

The first reason is that the letter Alif is written like a numeral—its shape directs attention towards that Sacred Being who is One and Unique. Through it, the sign of divine Oneness (Ahadiyyat) becomes manifest.

…

…

In the Rig Veda it is said:

Not two—He is One, Brahman.

In the Sikhs’ Mul Mantar (the foundational formula), the glory of divine Oneness is introduced in the following way:

Ik (Alif) Onkar, Satnam, Karta Purakh,

Nirbhau, Nirvair, Akaal Moorat,

Ajooni, Saibhang, Gur Prasad

That is:

Ik (Alif): One, the Absolute Truth, All-Powerful,

Fearless, Without Enmity, Eternal, Everlasting,

Without form, Self-subsisting—known through the Guru.

You will have noticed that in this Mul Mantar, no verbal description is used to declare God’s Oneness; instead, a single vertical line is drawn—resembling both the letter Alif and the numeral one. This method was adopted so that no confusion or doubt could remain.

The second point about Alif is that it is the first letter of God’s personal name, Allah. That is why many Allah-lok (Friends of God) begin their discourse by saying “Alif Allah”:

I found Alif Allah—Be is enough for its share;

Whoever seeks other than the Truth belongs to desire. — Sultan Bahu

Bulleh Shah says:

Alif Allah dyed my heart—

I needed no other news of my Lord.

What we studied was investigative knowledge;

Here there is only one true letter.

All other disputes are unnecessary.

Here, the single letter Alif is declared to be the true reality. Explaining this, Sultan Bahu writes in Haq-ul-Fuqara Khurd that it is only Alif which, when read, unites the reader with God. Duality (doʾi / thanviyyat) disappears; whoever becomes intimate with Alif, for them the door of knowledge opens through the knowledge of Alif itself.

…

They read and read, but knowledge breeds arrogance,

the clerics seek grandeur;

Like clouds of the monsoon they wander,

books clutched beneath their arms.

Wherever they see goodness, they read lofty words;

In both worlds, Bahu, they are disgraced—

those who sell what they have consumed for profit.

At this point, the statement “al-‘ilm hijab al-akbar” (knowledge is the greatest veil) finds its proper meaning. This veil comes into existence only when a person does not undertake the quest to attain true knowledge (ma‘rifat) of the Divine Oneness of Allah Almighty. That Oneness is attained through studying the knowledge of Alif; it is this single letter that points the way to the path of love. One who becomes a traveler on this path—according to Sultan Bahu—has their ordinary, common self erased, and through passing by the Divine attributes, ultimately becomes annihilated (fana) in the Divine Essence itself, becoming one with it.

(Tamahi, “Ankh,” Kanganpur — April–May–June 1991)

Seen at first glance, this excerpt from Asif Khan’s essay “Alif Allah” possesses a spiritual, cultural, and linguistic beauty. Yet when examined through the lens of the materialist dialectical conception of history, this very beauty reveals itself as an ideological operation—one within which several crucial historical questions are muted. The most fundamental feature of this essay—and simultaneously its most fundamental problem—is the suspension of historicity. The Rig Veda, the Aranyakas, the Gita, Sufi poetry, and the foundational texts of Sikhism are all placed on a single metaphysical plane and presented as evidence of the eternal grandeur of “Alif.” In this way, different social formations, different relations of production, and different historical crises dissolve into a single spiritual unity.

For materialist dialectical consciousness, the primary question that arises here is this: why does “the One,” or “Alif,” emerge in every historical epoch, and what social necessity does this emergence answer? Instead of raising this question, Asif Khan’s text turns “Alif” into a transcendent, eternal, and ahistorical truth. As a result, the meaning of ekam sat in the tribal society of the Rig Veda, the conceptual advance of prana = brahman in the period of the Aranyakas, the akshara of the Gita in the background of moral and state crisis, “Alif” among the Sufis as a challenge to clericalism and feudal oppression, and Ik Onkar in Sikhism as a negation of caste and religious monopoly—all are severed from their specific material and social contexts and transformed into a single, uninterrupted narrative of monotheism.

It is precisely at this point that the essay enters a Punjabi nationalist metaphysical sensibility. Punjab’s history ceases to be a history of class struggle, state formation, land relations, and modes of production, and instead becomes the history of an unbroken spiritual unity. The Sufi is always a symbol of resistance, the cleric always a symbol of oppression, and “Alif” always the key to salvation. From a materialist dialectical perspective, this is a process of flattening history, in which contradictions dissolve into love and relations of power disappear from view.

Statements such as “al-‘ilm hijab al-akbar” (knowledge is the greatest veil) must also be read in this context. Asif Khan presents this phrase as a spiritual declaration against bookish knowledge, clerical arrogance, and formal religion. But materialist historical consciousness immediately asks: whose knowledge was this? Which institutions, which classes, and which relations of power did it serve? In the Sufi tradition, this slogan was not directed against knowledge as a human product, but against the knowledge institutionalized in the madrasa, the qazi, and feudal state religion—knowledge that legitimized authority, taught obedience rather than inquiry, and sanctified social inequality. Because this distinction is not clearly maintained in the essay, there emerges a danger that critique of knowledge may slip into the glorification of ignorance or a metaphysical surrender disguised as spirituality.

A similar problem appears when references from the Rig Veda or the Aranyakas are directly absorbed into formulations such as “He is One, Brahman” or “the essence of all letters is Alif.” This becomes an anachronistic move—absorbing the intellectual संकेत (indications) of tribal and pre-feudal societies into a later, fully formed metaphysical monotheism. In this process, the intellectual struggles, uncertainties, questions, and social contradictions of ancient texts vanish, and those texts are reduced to raw material for later religious and nationalist interpretation.

From the standpoint of materialist dialectical consciousness, Asif Khan’s essay thus produces a double and contradictory outcome. On the one hand, it weaves together the internal unity of Punjabi Sufi tradition with great aesthetic power, creating a compelling cultural narrative. Its linguistic beauty, continuity of tradition, and intensity of spiritual experience allow the reader to encounter Punjabi Sufism as a living, coherent, and meaningful whole. In this sense, it stands as an influential and legitimate representation of Punjabi cultural consciousness.

On the other hand, the same narrative sacrifices historical temporality in exchange for spiritual and aesthetic coherence. Tribal, pre-feudal, feudal, and colonial social formations are absorbed into a single metaphysical horizon. Social and class contradictions, relations of land and production, state formation, and dynamics of power are resolved into the language of love, unity, and spirituality. “Alif” ceases to be a question and becomes an answer—an answer that silences inquiry instead of provoking it, and turns history from a dialectical struggle into a spiritual continuum.

The materialist dialectical alternative reading intervenes precisely here. It argues that from the Rig Veda to the Sufis, “Alif” is not the name of an eternal metaphysical truth, but a historically recurring intellectual attempt to bind together disintegrating social relations. At different moments it becomes a symbol of tribal cohesion, a moral refuge during feudal crisis, a protest against clerical and state religion, or a negation of caste hierarchy. But once “Alif” is detached from its historical and material conditions, it no longer signifies resistance or questioning; it turns into cultural consolation—a consolation that renders society bearable rather than intelligible. At this point, materialist dialectical consciousness does not reject “Alif,” but returns it to history and restores it as a question, so that unity becomes a path to liberation rather than a veil.

Asif Khan’s essay is undoubtedly a beautiful, eloquent, and powerful document of Punjabi spiritual consciousness, one that gathers the aesthetics of Sufi tradition, the symbolism of unity, and cultural memory into a compelling narrative. It captivates the reader and presents “Alif” as a spiritual symbol opening multiple windows of meaning, love, and identity. Yet for materialist dialectical consciousness, this moment demands not only appreciation but interrogation. It requires that we be inspired by “Alif,” but also that we place it in the dock of history, society, and power. For the moment “Alif” ceases to be a question and becomes a final answer—severed from its material conditions—it no longer symbolizes unity but becomes a veil concealing social contradictions, class struggle, and historical dialectics. Liberation, for materialist dialectical consciousness, lies precisely in sharpening the questioning edge of “Alif” alongside its beauty—so that it becomes not consolation but consciousness; not a curtain, but a window.

When examining this essay through the materialist dialectical conception of history, it is crucial not to detach it from its temporal, political, and intellectual context. One must remember that Asif Khan wrote this essay in the early 1990s, a moment when Pakistan—especially Punjab—had not yet fully emerged from the deep imprint of General Zia-ul-Haq’s religious dictatorship. Sectarianism, jihadism, the politics of Sharia enforcement, and the organized discourse of political Islam had gravely damaged Punjab’s long-standing traditions of religious tolerance, cultural coexistence, and Sufi pluralism. In such a context, essays like “Alif Allah” were not merely literary or spiritual writings but acts of cultural resistance.

Asif Khan’s essay is part of a broader progressive Punjabi literary discourse that took shape in the 1970s and 1980s in response to reactionary literary narratives. These reactionary discourses were produced on the one hand by right-wing political Islamists—particularly writers influenced by Jamaat-e-Islami such as Naseem Hijazi—and on the other by figures like Hasan Askari, Saleem Ahmed, and Intizar Hussain, who, while not directly aligned with Jamaat-e-Islami, nevertheless foregrounded the Two-Nation Theory, Urdu centrality, and a metaphysical conception of Islamic civilization. In response, the Punjabi progressive literary current highlighted anti-clerical, anti-qazi, and anti-priestly elements found in local history, Vedic texts, ancient scriptures, and Sufi traditions, presenting them as an internal, continuous Punjabi cultural lineage. The materialist dialectical problem emerges here: these elements were largely severed from their specific historical material conditions, social contradictions, and relations of production. The Rig