Dear Brother Safdar,

Greetings—and a very happy birthday to you!

I’m currently confined to bed, suffering from sciatica. Only now do I realize how excruciating this condition truly is. My father once suffered the same ailment during my student days; he would groan day and night, and though I was concerned for him, I never fully grasped his pain—until now. It’s 3:30 AM as I write this, and the pain has stolen my sleep. Writing to you is my way of distracting myself.

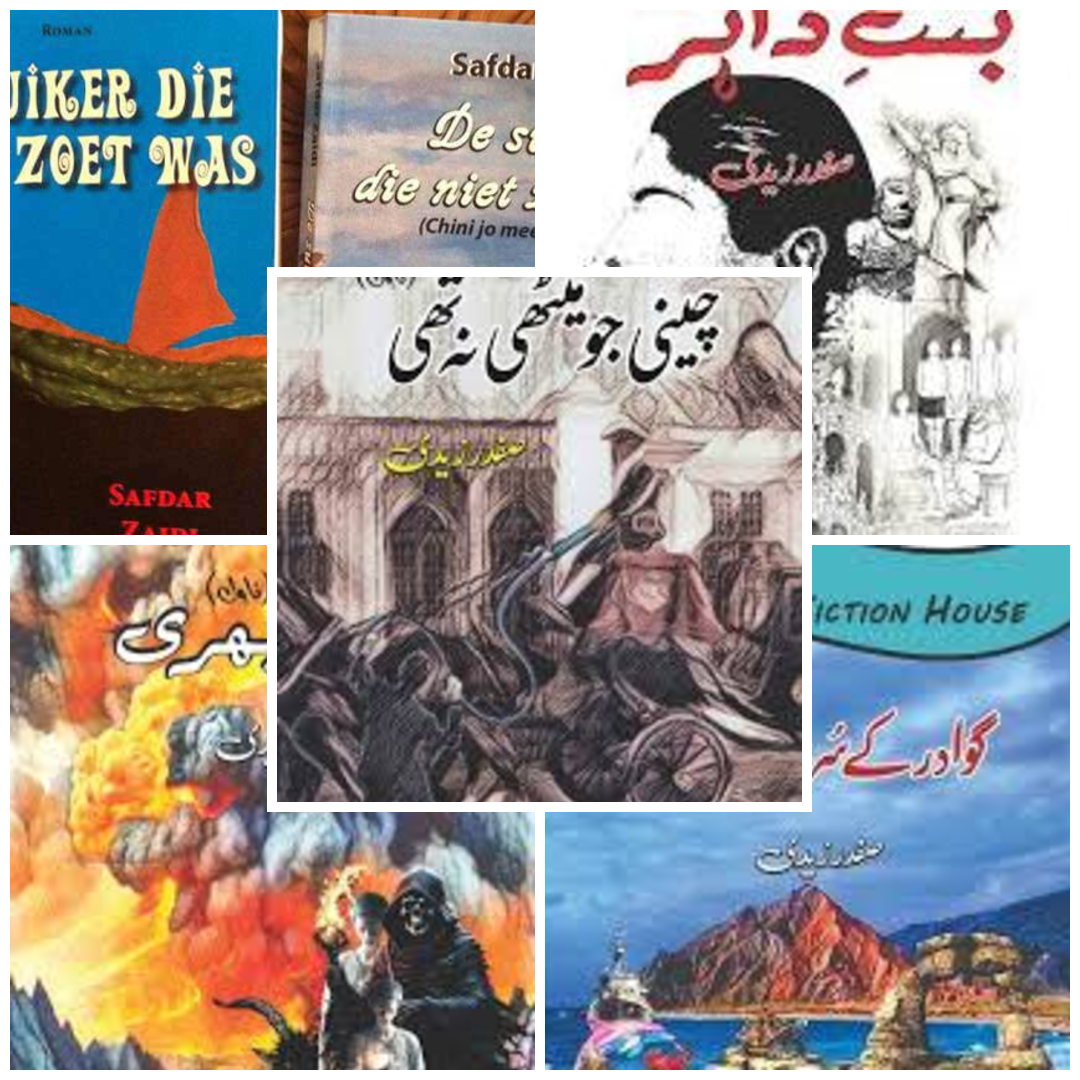

I’ve been following your travels through Italy via your posts on Facebook. You’ve done a great job producing the audiobook of Bint-e-Daher. I’d encourage you to create audiobooks of Cheeni Jo Meethi Na Thi and Bhag Bhari as well. With AI-powered dubbing tools now available on platforms like YouTube, your novels could reach global audiences in multiple languages.

The plot of your upcoming novel sounds promising. Your immersion in Amazonian folklore, meeting writers there, exploring the terrain—this journey has stirred great curiosity. We eagerly await what emerges from your literary satchel this time.

Recently, I read an interview with a writer who had studied Balzac’s works extensively. He remarked that The Human Comedy was, in Balzac’s view, authored not by him but by French society itself—he was merely its scribe. He also noted that sexuality in Balzac’s work remained an enigma, like the Sphinx’s riddle—never fully explored. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this someday.

Balzac once envisioned a peculiar business idea—he wanted to rent a shop on Boulevard des Italiens and sell colonial goods under the name “Honoré de Balzac, Grocer”, believing the scandal would drive mass sales. He toiled by day seeking money, and by night, donned a monk’s robe to write, fuelled by endless mugs of coffee. He died at fifty.

Reading this reminded me of Manto—who, like Balzac, poured his soul into stories just to earn a living, and died far too young. Both struggled between short stories and drama.

Both faced moral outrage for confronting sexuality in their work.

Your Bint-e-Daher too sparked backlash—some Sindhi nationalists saw its bold female sexuality as dishonoring “the daughter of Sindh.” Religious conservatives called it an attack on Muhammad bin Qasim’s legacy. But I believe great novels are always layered, open to diverse interpretations. Bint-e-Daher is such a novel—its richness will reveal itself over time.

These days, I’m reading Dhai Haroof, Abbas Zaidi’s compelling short story collection, first published in the U.S. I’m also studying Martin Hinds’ The Murder of Uthman ibn Affan, deeply impressed by his method of historical critique. Can our society ever reflect on such critical work without invoking blasphemy?

Your earlier post on Sayyid DNA and the presence of African genes caused some consternation too. But what does outrage achieve, other than raising our blood pressure? Our society often fears creativity and tries to crush it.

I’m also reading Muzaffar Ali Syed’s literary criticism and two new books on political economy. My current focus is Marx’s idea of the Asiatic Mode of Production, especially how Indian, Chinese, and Japanese Marxists have interpreted it. Surprisingly, many Indian scholars ignored Marx’s Ethnological Notebooks and relied solely on his New York Tribune articles. Irfan Habib admitted he didn’t have access to those notes while researching the Mughal administrative system.

Wherever ideological rigidity takes root—be it in religion, Marxism, or liberalism—it breeds dogma. A dogmatic Marxist or liberal is just another stagnant swamp, stinking with arrogance.

I’ve said quite a bit. Once again, heartfelt birthday wishes. May your creativity continue to bloom, and may you return from your travels with new stories for us all.

Warm regards,

Your brother,

Aamir Hussaini

Jam-e-Safaal House

House No. 345, Mohallah Tariqabad, Khanewal

Dated: June 26, 2024

About the Correspondents

Safdar Naveed Zaidi is a Pakistani-born writer currently residing in the Netherlands. Born in Karachi, the capital of Sindh, he is professionally an agricultural scientist. As a novelist, he has authored four published novels to date. His literary work often engages with social, cultural, and historical themes, reflecting both his deep roots in Sindh and his global perspective shaped by his life in Europe.

Muhammad Aamir Hussaini is a poet, writer, and translator based in Pakistan. He has published four translations of English and Spanish novels into Urdu, and is the author of two original books. He also edited a significant volume documenting the sectarian violence against the Shia community in Pakistan. By profession, he is a journalist and currently serves as the Bureau Head for The Daily Minute Mirror, an English-language daily published from Lahore, overseeing the Multan region.